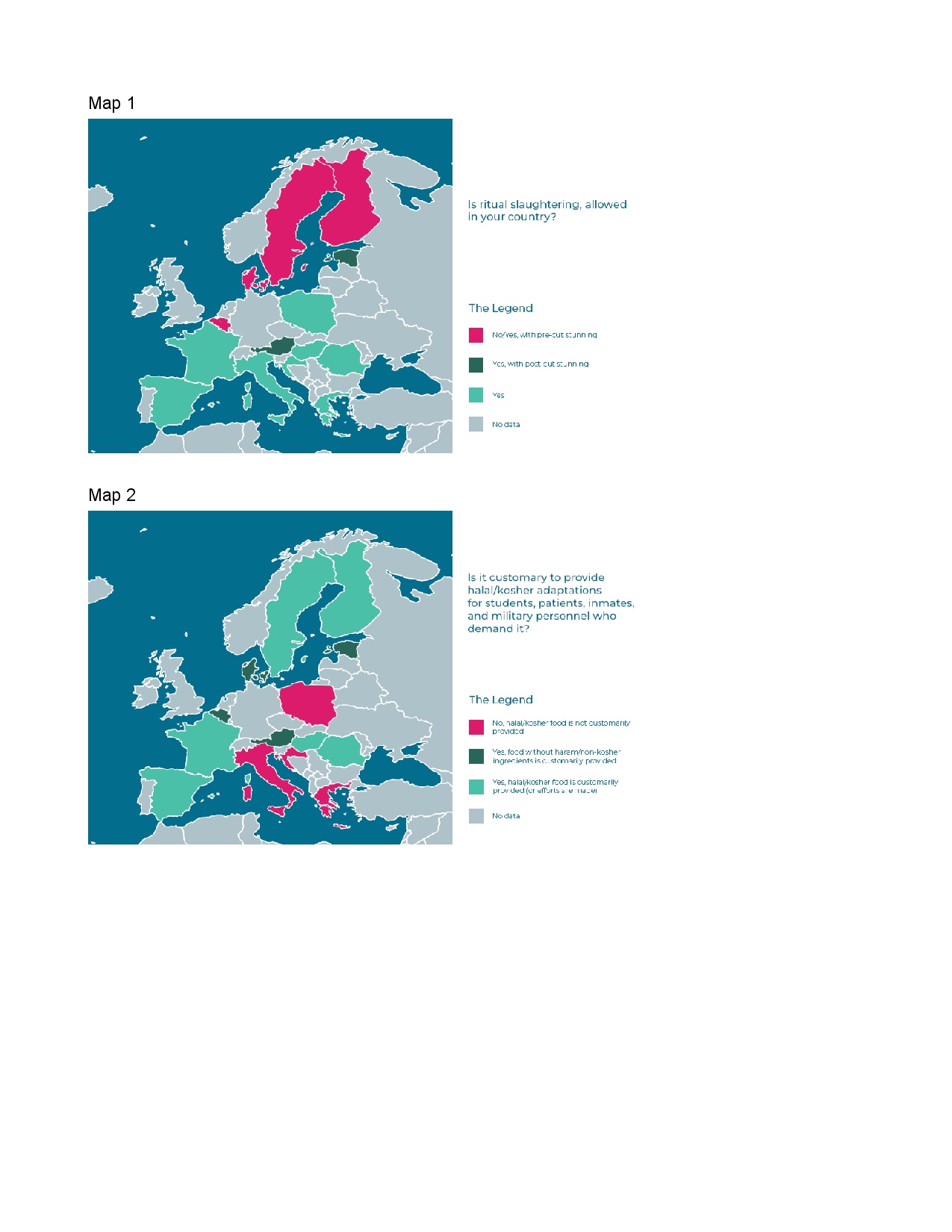

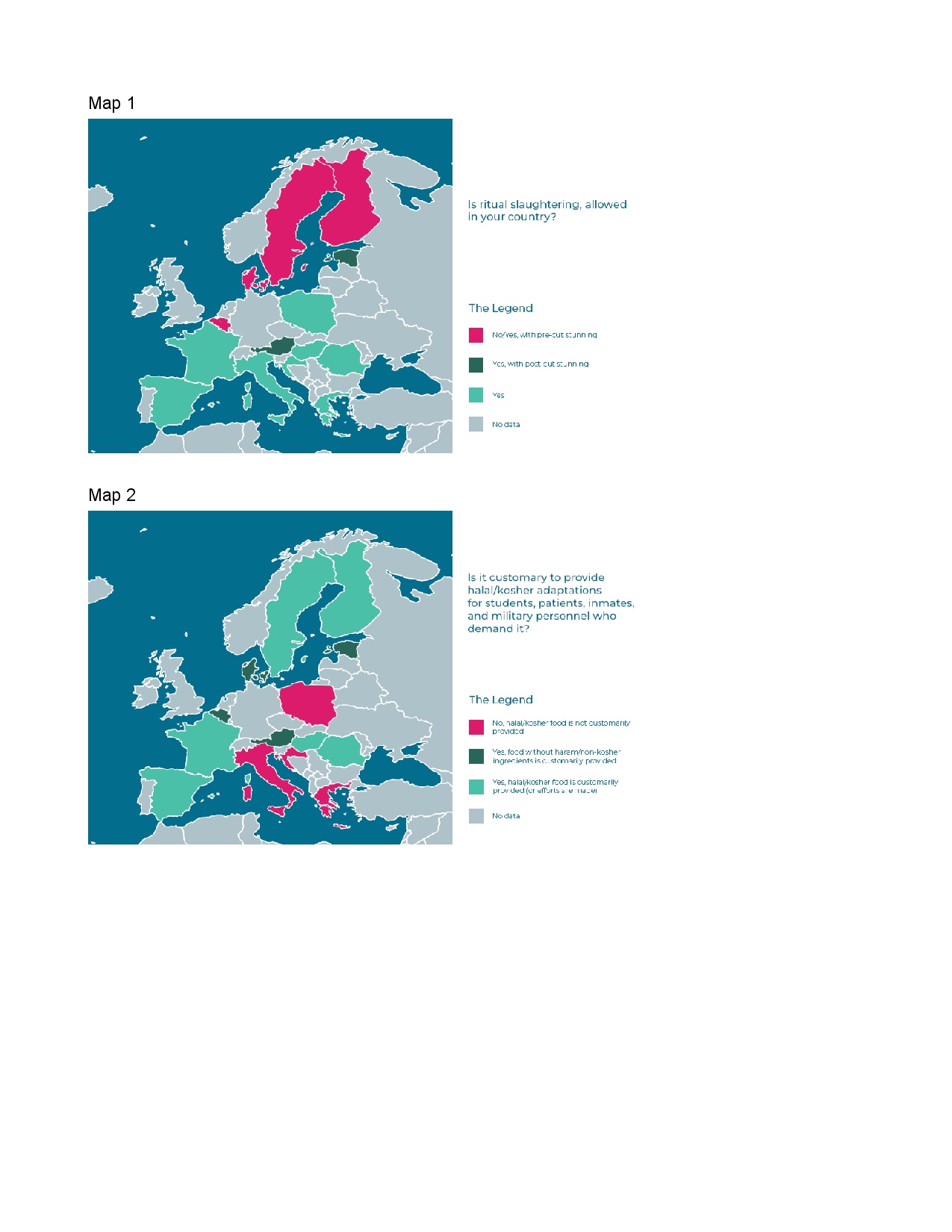

1. Most European countries allow for ritual slaughter without previous stunning. Among the countries studied by the Atlas, only Wallonia and Flanders in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Greece, and Sweden have regulations limiting religious slaughter (see Map 1).

2. All of the limiting countries allow for import of kosher/halal meat.

3. Judgment C-336/19 of the Court of Justice of the European Union made it possible for the state to prohibit the slaughter of animals without stunning even in the context of ritual slaughter. This may lead to legislative changes in the next years.

4. No countries have legal obligations to provide kosher/halal dietary adaptations in public institutions like schools, universities, hospitals, military, or penitentiaries.

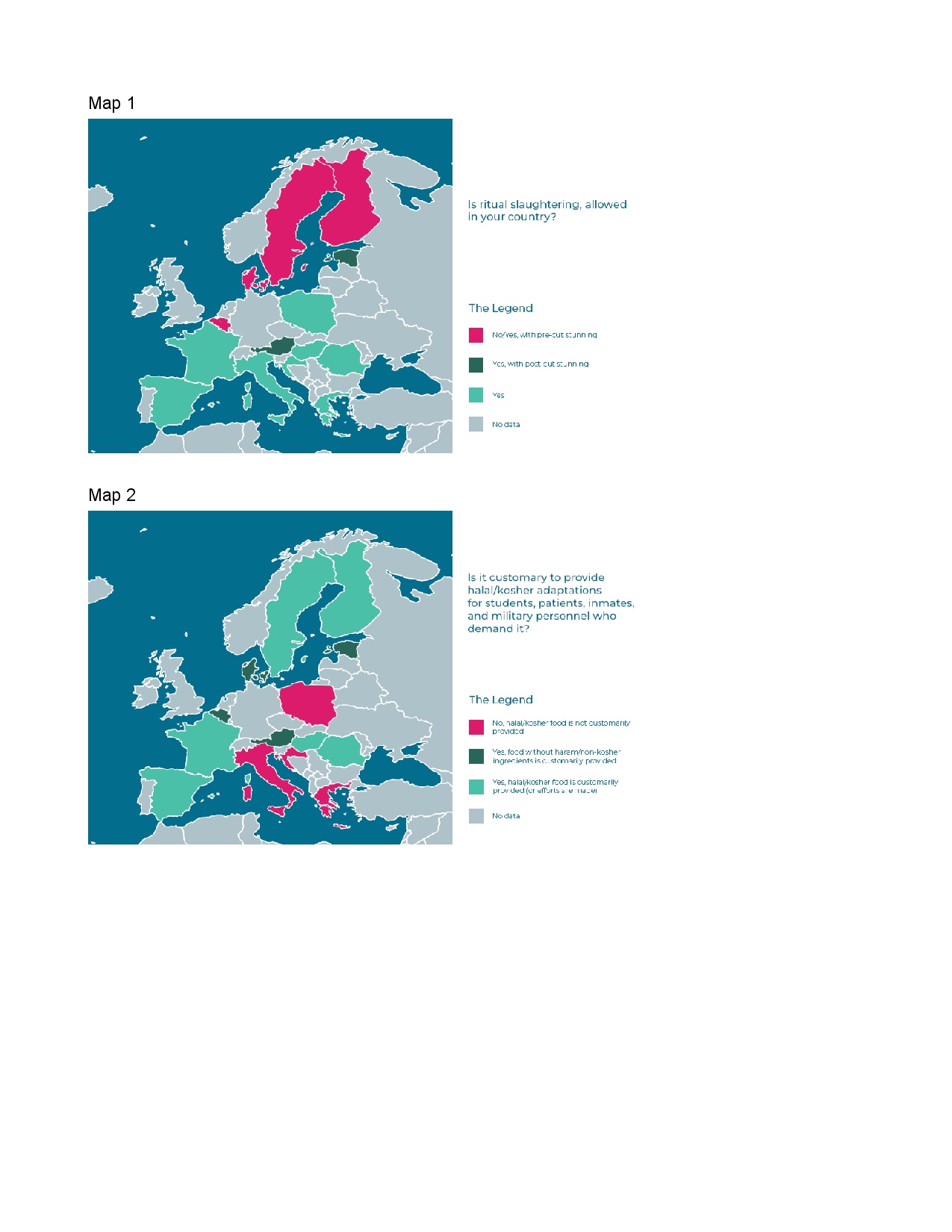

5. In most countries, the actual provisions are not standardized at the central level and very much depend on individual institutions. Schools, universities, and military are usually the most adaptive to the requests of religious or belief minority members. However, most countries customarily provide or make efforts to provide either meals adapted to kosher/halal requirements, or without non-kosher/haram ingredients (see Map 2).

6. In most countries, there are no problems in bringing kosher/halal food from home or receiving it from third parties. Prisons are the most often exception, due to their penitentiary regimes.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Since many public institutions do not provide kosher/halal meat and do not allow to obtain it from alternative sources, offering a vegetarian option should be compulsory in public school, prison, healthcare institution, and Army canteens. However, it should be noted that this is not an optimal solution – for some strands of Judaism, meals cooked by non-Jews are not kosher, and thus require further adaptation.

2. Alternative solutions to the current pre-cut stunning should be sought that would comply with religious requirements without compromising animal welfare.

3. Allowing for bringing kosher/halal foods by third parties, including in penitentiaries, could be another way of promoting rights of religious minorities without significantly increasing the efforts required from public institutions.

What we are talking about

Ritual slaughter refers to a broad range of practices that involve slaughtering livestock in line with ritual norms and in a ritual context. While various cultures and religious traditions practiced ritual slaughter in some form over time, in the contemporary European context ritual slaughter has been predominantly associated with Jewish and Muslim communities and the kosher/halal meat production.

Based on Torah and Talmud, Jewish dietary regulations (Kashrut) differentiate between two types of food domains: plants and animals. While practically all plant foods are consumable, once they have been carefully inspected for contaminants, there are significant dietary restrictions concerning animal foods. For the animal to be considered kosher, it needs to have split hooves and chew its cud. Moreover, it needs to be slaughtered in a specific manner. A subset of Kashrut rules, schechita, dictates the rules according to which slaughter needs to be performed by a specially trained slaughterer, schoichet. The two basic rules for the slaughter to be kosher are:

1. The animal must be alive before the ritual begins.

2. The ritual follows a specific order, in which specific blood vessels must be cut in a specific place to ensure that the animal becomes unconscious and insensitive, with the use of a specific sharp tool called chalaf. The slaughter is then followed by an inspection of the body and the internal organs for abnormalities (terefot), and porging (nikur), which removes blood and excess fat.

Islamic dietary regulations divide foods into two basic categories: lawful (halal) and unlawful (haram) foods. This is supplemented by discouraged (makrooh) and suspected (mashbooh) foods. In principle, all foods are considered halal unless specifically designated haram in the Quran or Hadiths. Alcohol, pork, blood, dead meat, and meat that has not been slaughtered in line with the Islamic rules are explicitly forbidden in the Quran, while Islamic jurisprudence distinguishes more haram foods based on the interpretation of other passages in the Quran. Shari’ah, Islamic law, regulates the rules for the animal slaughter to produce a purified meat – zabiha or dhabiha – which led to concrete certification systems. These rules provide a complex set of guidance on issues such as halal breeding, animal welfare, stunning, slaughterer, the method of slaughtering, invocation, packaging, labeling, and, finally, retailing.

While both Jewish and Islamic ritual practices share a lot of similarities, they differ in one important aspect: the approach to stunning of the animal. While reversible stunning, post-cut stunning, and simultaneous stunning are discussed as possible within both traditions, the most effective method of stunning, pre-cut stunning, permanently damages the animal’s body, and thereby conflicts with the prescriptions that require the animal to be fully alive before the slaughter begins. The dominant interpretation of the Jewish law views it as a potential impairment of animal’s perfection, and thus forbids it. Islam is more divided on the issue, which means that some Muslims accept an animal killed with pre-cut stunning as halal, while others do not.

Thus, while both ritual practices account for animal welfare by attempting to minimize the suffering of the slaughtered animal, the opposition to pre-cut stunning led both traditions into conflict with the animal welfare movements. As the requirement to stun animals before slaughtering became the dominant principle, the exceptions for ritual slaughter began to be subject to negotiation. The earliest legislation forbidding ritual slaughter by requiring stunning dates to the 19th century and then was followed by on and off legislation in other countries in Europe. The issue has been complicated further, as many legislative proposals were introduced, supported, or promoted, by antisemitic movements, which, more recently, have acquired a more Islamophobic character. This led to the suspicions which proposals were just an effort at balancing animal welfare and religious freedom, and which were covert attacks on the latter.

According to a 2020 poll made by Savanta ComRes for the Eurogroup for Animals, the majority of Europeans supports the requirement to stun the animals before slaughtering, without exception for religious reasons (87% agree), although they want to prioritize funding for alternative practices that would comply with religious requirements without compromising animal welfare (80% agree). This is in line with the scientific consensus around the optimal methods for reduction of animal suffering (see reading suggestions below). In the last decade, Slovenia banned ritual slaughter altogether, while Denmark, Wallonia and Flanders introduced pre-cut stunning requirements. This led to significant criticism from Muslim and Jewish communities. For example, in response to the legislative proposals in Belgium, which required a reversible stunning procedure even in the context of ritual slaughter, several Muslim and Jewish organizations introduced an annulment appeal to the country’s Constitutional Court, which, in turn, referred a preliminary question to the Court of Justice of the European Union. The 2020 European Court of Justice judgment in the case C-336/19 sided with the Belgian region of Flanders, acknowledging the right of the EU Member States to prohibit slaughter without stunning, even in the context of ritual slaughter. This led to broad public discussion on the topic in the EU, including EU-wide consultations organized by the European Commission in 2022.

Five questions to the National Legal Experts

To provide a clearer picture of the current state of the legislation and practice concerning ritual slaughter the Atlas of Religious or Belief Minority Rights asked five questions to the National Legal Experts.

1. Is ritual slaughtering allowed in your country?

This question asks about the current regulations concerning exceptions for animal slaughter: no stunning required, post-cut stunning, simultaneous stunning, and pre-cut stunning.

2. If ritual slaughtering is forbidden, is importing from abroad ritually slaughtered food allowed?

As an alternative to the exceptions for religious slaughter, some countries, for example Denmark, proposed to allow for kosher/halal meat import.

3. Are public schools, hospitals, prisons, and the army obliged to provide halal or kosher food to students, patients, inmates, and military personnel who demand it?

This question asks whether individuals have the right to request specific dietary provisions within these institutions that comply with their religious requirements, which will oblige the institution to provide them.

4. If there is no obligation, is it customary to provide halal/kosher adaptations for students, patients, inmates, and military personnel who demand it?

This question asks about the actual provisions. The questions could have been answered in three ways: yes, halal/kosher food is customarily provided (a positive provision); yes, food without haram/non-kosher ingredients is customarily provided but not halal/kosher food (a negative provision); no, neither halal/kosher food nor food without haram/non-kosher food is customarily provided. We allowed for differentiation between institutions.

5. If there is no obligation, can students, patients, inmates, and military personnel consume halal or kosher food brought from home or provided by someone other than the public institution (e.g., their religious organization)?

Most kitchens within public institutions lack means for following strict rules of Kashrut. Thus, some institutions, for example some Austrian and Belgian penitentiaries, reach out to Jewish organizations to supply meals for their Jewish population.

Ryszard Bobrowicz

Focus Ritual Slaughter: Questionnaire

RESOURCES

For a review of different European legislative regimes see

United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (2020, October). Legislation Factsheet: Ritual Slaughter Laws in Europe

Eurogroup for Animals (2021, May). Slaughter without Stunning (Position Paper)

For databases of applicable legislation see

the Legislation Database of the Global Animal Law GAL Association

the FAOLEX Database of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation

For scientific approaches to stunning and animal welfare see

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) (2004, July 6). Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW) on a request from the Commission related to welfare aspects of the main systems of stunning and killing the main commercial species of animals.The EFSA Journal, 45, pp. 1-29

Ferraro, F. (2017). Ritual Slaughtering Vs. Animal Welfare: A Utilitarian Example of (Moral) Conflict Management, in M. Rawlinson, & C. Ward (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Food Ethics. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 305-314

For a brief review of the role of ritual slaughter for religious identity see, for example

Bonne, K., & Verbeke, W. (2008). Religious values informing halal meat production and the control and delivery of halal credence quality. Agriculture and Human Values, 25, pp. 35-47

Greenfield, H. J., & Bouchnick, R. (2010, January). Kashrut and Shechita – The Relationship Between Dietary Practices and Ritual Slaughtering of Animals on Jewish Identity, in L. Amundsen-Meyer, N. Engel, & S. Pickering (eds.), Identity Crisis: Archaeological Perspectives on Social Identity. Proceedings of the 42nd (2010) Annual Chacmool Archaeology Conference, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta. Calgary: Chacmool Archaeological Association

See also

https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/farm/slaughter/religiousslaughter

" />Messner, F. (ed.), Dictionnaire du Droit des Religions, s.v. «Abbatage rituel». Paris: CNRS Editions, pp. 3-17

Martínez-Ariño, J., & Zwilling, A-L (2020). Religion and Prison: An

Overview of Contemporary Europe. Cham: SpringerLerner, P., & Rabello, A. M. (2006). The Prohibition of Ritual Slaughtering (Kosher Shechita and Halal) and Freedom of Religion of Minorities. Journal of Law and Religion, 22(1), pp. 1–62

Se hai dimenticato la password, richiedila ora inserendo il tuo indirizzo email (lo stesso che usi per comunicare con METALWEEK). La riceverai direttamente nella tua casella di posta.

1. While in most countries there are no general restrictions on wearing RBSs in the workplace or in public spaces, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, and France have enacted provisions that prevent people from circulating in public spaces with one's face covered, thus limiting the right of Muslim women to wear burqas or niqabs.

2. In Belgium and France public employees cannot wear RBSs in the workplace.

3. In France and Hungary the official display of RBSs in prisons, healthcare facilities and army barracks is forbidden. In Austria, Greece, Italy, Romania, Spain, where there is no regulation that imposes or forbids the display of RBSs by these institutions, the symbols of the majority religion are frequently displayed.

4. Equal treatment is better ensured if there are no restrictions on the wearing of RBSs in the workplace or in public spaces, and no obligations to officially display RBSs in prisons, hospitals and army barracks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. General bans of the right to wear and/or display RBSs in public spaces and in the workplace may easily result in discrimination of RBMs and should therefore be avoided.

2. States should encourage the pursuit of solutions through the involvement of all stakeholders. A general ban on the displaying of religious / belief symbols by public institutions, as well as a general obligation to display the symbols of the majority religion only, does not amount to promotion of RBM rights.

RISKS OF DISCRIMINATION

In Austria, Belgium, Denmark and France, a general ban on the wearing of religious symbols that cover the face in public places -regardless of whether the limitations prescribed by Article 9.2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) apply- is in force. Although an international standard cannot be clearly identified as the case-law of international courts and bodies is not consistent, such ban may easily become a cause of discrimination.

In the EU countries the issue of RBSs has become topical in the last 30 years. At first it concerned female students wearing the Islamic headscarf at school, then women wearing burqas or niqabs in public places or in the workplace, and later the crucifix displayed in classrooms, not to mention the request of Pastafarians to have the colander recognized as their religious symbol. After years of legislative interventions and conflicting court decisions, a certain consensus has been reached on three points: wearing or displaying RBSs constitutes a manifestation of freedom of religion or belief which is protected by Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR); when certain conditions are met, however, it is lawful to limit or prohibit the exercise of this right; in any case, these limitations must not cause discrimination. In most countries of the European Union, the issue of RBSs is addressed through case law: the judge is in the best position to seek a "reasonable accommodation" between the different stakeholders. Only a few states have tried to solve the problem through the lawmaker's intervention: in most EU countries there are no rules prohibiting or authorizing the display of RBSs. The fact that the Atlas data are predominantly derived from the analysis of legislation explains why the results concerning RBSs are similar in many countries. These data therefore need to be supplemented by the examination of case law (which is outside the research scope of the Atlas).

According to international standards, wearing religious symbols is a manifestation of the right to freedom of religion or belief (see UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), CCPR General Comment No. 22: Article 18 (Freedom of Thought, Conscience or Religion), CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, 20 July 1993, para 6; Council of Europe: European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), Guide on article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights: Freedom of thought, conscience and religion, 31 August 2022 (last updated), Chapter II, nos. 99-116). Wide limitations may be legitimately applied on a number of grounds, including safety, security and secularism (Guide on article. 9), but limitations may not be imposed for discriminatory purposes or applied in a discriminatory manner [CCPR General Comment No. 22, para. 8, p.3].

RBSs in the workplace (Clusters A and B)

The right to wear and/or display RBSs in the workplace is subject to different conditions depending on whether the employer is a public or private subject. If the employer is public, some states prohibit the wearing or display of RBSs on the basis of the principle of neutrality of public institutions; if private, the potential of any RBSs worn or displayed by an employee to damage the interests of the company is of central importance. Recently, the Court of Justice of the European Union has ruled that, if certain conditions are met, a public employer may prohibit employees from wearing religious symbols if the prohibition is justified by a desire to establish "an entirely neutral administrative environment" (Judgment in case C-148/22 OP v. Commune d'Ans) and has extended the application of the neutrality principle to the private sector, potentially reducing the right to wear or display RBSs (Judgment in Joined Cases C-804/18 and C-341/19 WABE and MH Müller Handel). The courts have examined the cases before them from two points of view: on the one hand, respect for freedom of religion, and on the other, prohibition of discrimination. The combination of these two criteria has not always been smooth.

Generally speaking, the Atlas considered that the RBM rights are better promoted when there are no legislative provisions denying or limiting a priori the right to wear and/or display RBSs, leaving the field open to judges' evaluation. For this reason, a negative score (ranging, depending on the case, from -1 to -0.50) was given to those countries that include norms of this type in their legal systems.

According to the Recommendations of the Forum on Minority Issues at its sixth session: Guaranteeing the rights of religious minorities, 26 and 27 November 2013 (A/HRC/25/66, n. 30), [e]conomic actors, including private businesses, as well as bodies representing employees, such as trade unions, should ensure that religious minorities and their specific religious requirements are reasonably accommodated in the workplace” (see also Guide on article 9, nos. 99-116; CCPR General Comment No. 22: para 4).

Accepted limitations to the right to wear RBSs include secularism (see Guide on article 9, no. 112: "[…] States may rely on the principles of State secularism and neutrality to justify restrictions on the wearing of religious symbols by civil servants at the workplace […]") and the protection of the company's specific commercial image weighed up against the individual’s right to manifest his or her religion (see Guide on article 9, no. 116; see also European Court of Human Rights, Eweida and Others v. the United Kingdom, Application nos. 48420/10 et al., 27 May 2013, paras. 94-95)..

RBSs and members of Parliament, judges and police officers (Cluster C)

Some subjects perform public functions of particular importance and sensitivity. As noted by the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, “this may require complete neutrality as between different political and religious insignia; in other instances, a multi-ethnic and diverse society may want to cherish and reflect its diversity in the dress of its agents.” [Human rights in Europe: no grounds for complacency, Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2011, Chapter 1, p. 41].

Both options are legitimate from the point of view of international standards. The Atlas examines three categories of subjects (MPs, judges, and police officers) and considers whether special rules apply to them. The need for special rules has been widely debated, especially in relation to judges, but in the countries considered by the Atlas, only France (for members of Parliament) and Denmark (for judges) have enacted restrictive rules.

RBSs in public spaces (Cluster D)

Some states prohibit the wearing of particular RBSs (specially those that cover the face) in public spaces (streets, squares, etc.). The reasons most frequently cited to justify this prohibition are security and, with particular reference to burqa and niqab, women's rights. The ECtHR has also held that the ban of full-face veil in public places “can be regarded as proportionate to the aim pursued, namely the preservation of the conditions of "living together" as an element of the "protection of the rights and freedoms of others” [S.A.S. v. France, Application no. 43835/11, 1 July 2014, para 157].

Also in this case, a negative score was given to countries that have enacted restrictive or prohibitive general legislation, thus reducing the possibility of resolving any conflicts through case law.

In some countries, regulations have been introduced that prohibit the public from wearing or displaying RBSs inside public institutions (hospitals, courts, etc.) for security reasons or to respect the neutrality of these places. The Atlas has considered whether there are any special rules that differ from those in force for public places in general. There is no evidence of the existence of such rules at the national level, although in some countries they are in force at the local level. Finally, specific public spaces where security requirements are especially stringent, such as airports, were considered. Here, too, the existence of particular rules beyond the obligation to temporarily remove religious symbols that prevent the identification of a person or security checks, was not found.

The Council of Europe has expressed the opinion that

[…] Article 9 of the Convention includes the right of individuals to choose freely to wear or not to wear religious clothing in private or in public. Legal restrictions to this freedom may be justified where necessary in a democratic society, in particular for security purposes or where public or professional functions of individuals require their religious neutrality or that their face can be seen.

On the specific issue of the full-face veil, it has added that “a general prohibition of wearing the burqa and the niqab would deny women who freely desire to do so their right to cover their face” [Council of Europe: Parliamentary Assembly, Islam, Islamism and Islamophobia in Europe, Resolution 1743(2010), 23 June 2010, no. 16].

The ECtHR has established that prohibiting the wearing of religious clothing or symbols in public places may constitute a violation of Article 9 ECHR (Ahmet Arslan and Others v. Turkey, Application no. 41135/98, 23 February 2010,). It has also ruled that the wearing of an item of clothing intended to cover the face may be legitimately restricted or prohibited by a State, even if this item is deemed to be a religious symbol: in fact “the barrier raised against others by a veil concealing the face" may constitute a "breaching [of] the right of others to live in a space of socialization which made living together easier” (S.A.S. v. France para 122).

Official display of RBSs in prisons, health facilities and army barracks (Cluster E)

In some countries there is an obligation to display the symbols of a religion (usually the majority religion) in prisons, health facilities and barracks; in others the official display of RBSs is possible but not compulsory and still in others is forbidden. The criteria that were applied to assess these different national situations are the same as those used in relation to official RBSs display in public schools (see the introduction to the policy area "RBM rights in public schools,” cluster D under “What we are talking about”).

Display of RBSs by inmates, patients, and military personnel in their private spaces (Cluster F)

In all EU countries inmates, patients and military personnel may display RBSs in their private spaces (bedside table, locker, etc.) without any restrictions.

For the issue of RBSs at school see the policy area "RBM rights in public schools".

Cristiana Cianitto and Silvio Ferrari

This guide provides some keys to interpreting the three indices (P-index, E-index and G-index) calculated on the basis of the Atlas data.

P-index (States)

1. Analysis of the data on religious or belief symbols (RBSs) indicates that most countries have not introduced general restrictions or prohibitions that prevent or make it difficult to wear RBSs in the workplace or in public spaces (see clusters A-D). Despite the fact that, from time to time, and in specific cases, the courts or local administrative authorities have subjected this right to some restrictions, there is no general legislative prohibition. On the other hand, such a prohibition is in force in four countries, Austria, Denmark, Belgium and France, where it is forbidden to circulate in public places with one's face covered (this prevents Muslim women from wearing burqas or niqabs). In France, moreover, public employees cannot wear RBSs in the workplace and members of Parliament cannot wear conspicuous RBSs (a similar prohibition also applies to students in public schools; this issue is considered within the policy area "RBM rights in public schools"), while in Denmark a similar prohibition applies to judges.

2. The display of RBSs by public institutions is the other major theme addressed within this policy area (see cluster E). The Atlas takes into consideration prisons, health facilities and army barracks (for the display of RBSs in public schools see the corresponding policy area). In relation to these places, the countries considered in the research can be divided into three groups. In some (France and Hungary) the display of RBSs is forbidden; in others there is no legislative prohibition but RBSs are not normally displayed (this is the case in Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Sweden); in the third group symbols of the Christian religion are usually displayed (crosses, crucifixes, icons, etc.) although there is no regulation that imposes such display. This is the case in Austria, Croatia, Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania and partially Spain. In some cases, RBMs share the symbols of the majority religion (for example in Italy the crucifix is the main symbol of the Catholic Church and the Lutheran Church). This fact, together with the absence of precise legislative references, has made the evaluation of the promotion of the rights of RBMs in each country particularly complex.

P-index (RBMs)

3. This index shows a cleavage between Christian and non-Christian RBMs. Overall, the RBMs that enjoy more favorable treatment are those that belong to the Christian religious family. The difference is mainly due to the fact that in some countries only Christian religious symbols are actually displayed in prisons, hospitals, and army barracks. Among non-Christian RBMs, Muslim communities are the worst off due to restrictions placed by some countries on hijab, burqa and niqab.

E-index (States)

4. Equal treatment of all RBMs is ensured in the countries where there are no restrictions on the wearing of RBSs in the workplace or in public spaces and no obligation to display RBSs in prisons, hospitals and army barracks: Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Hungary and Sweden. In the other countries, inequality is strongest in Austria where, in addition to the distinction between Christian and non-Christian RBMs that occurs in all countries where religious symbols are displayed in public institutions, an "anti-burqa" law that disadvantages Muslim women is in force.

G-index (States and RBMs)

5. This index confirms the data that has already emerged from the previous one. Sweden, Cyprus and Finland are the countries where the distance between the majority religion and religious minorities is less (in Estonia and Hungary there is no majority religion), and Austria the one where the distance is greater. Among the RBMs, Islam is the minority religion furthest from the position of the majority religion.

For the Council of Europe standing on the issue of religious symbols in public places (in particular concerning the wearing of burqa and niqab) see

Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly (2010, June 23) Islam, Islamism and Islamophobia in Europe, Resolution 1743(2010), nos. 15-17

Council of Europe: Parliamentary Assembly (2010, November 2 – 5). Islam, Islamism and Islamophobia in Europe, no. 3.13

The same issue has been addressed by

Hammarberg, T. (Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe)(2011). Human rights in Europe: no grounds for complacency. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, Chapter 2, pp. 39-43

ECtHR case law is summarized in

Council of Europe: European Court of Human Rights (updated on 2022, August 31). Guide on Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights: Freedom of thought, conscience and religion, nos. 99-116

A summary of the cases is contained in

Council of Europe: European Court of Human Rights (2021, December). Religious symbols and clothing

The decisions of the UN Human Rights Committee, which are often in contrast to those of the ECtHR, are analyzed in

International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) (2019, January). A Primer on International Human Rights Law and Standards on the Right to Freedom of Thought, Conscience, Religion or Belief, pp. 13-16

For a report mapping laws and legal developments restricting religious dress in the 27 countries of the European Union and the United Kingdom see

Open Society Justice Initiative (2022, March). Restrictions on Muslim Women's Dress in the 27 EU Member States and the United Kingdom: Current Law, Recent Legal Developments, and the State of Play. New York: Open Society Foundations

For an analysis of the issue of RBSs in the workplace see

Howard, E. (2017, November). Religious clothing and symbols in employment: A legal analysis of the situation in the EU Member States. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

Court of Justice of the European Union: the Research and Documentation Directorate (2016, March). Research Note: The wearing of religious symbols at the place of work

The issue of RBSs worn by judges is discussed by

Berger, B. (2016). Against Circumspection: Judges, Religious Symbols, and Signs of Moral Independence, in B. L. Berger, & R. Moon (eds.), Religion and the Exercise of Public Authority. Oxford and Portland: HART Publishing

About the official display of RBSs in prisons, healthcare facilities and barracks see

Stanisz, P., Zawislak, M., & Ordon, M. (eds.) (2016). Presence of the Cross in Public Spaces: Experiences of Selected European Countries. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing

and see also the resources listed in the introduction to the policy area “Spiritual assistance”

The issue of RBSs is discussed in the following books:

Cox, N. (2019). Behind the Veil: A Critical Analysis of European Veiling Laws. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing

Howard, E. (2021). Law and the Wearing of Religious Symbols in Europe. Abingdon: Routledge

Ferrari, A., and Pastorelli, S. (eds.) (2016). The Burqa Affair Across Europe: Between Public and Private Space. Abingdon: Routledge

Sobczyk, P. (ed.) (2021). Religious Symbols in the Public Sphere: Analysis on Certain Central European Countries. Budapest and Miskolc: Ferenc Mádl Institute of Comparative Law and Central European Academic Publishing

KEY FINDINGS

1. Most European countries allow for ritual slaughter without previous stunning. Among the countries studied by the Atlas, only Wallonia and Flanders in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Greece, and Sweden have regulations limiting religious slaughter (see Map 1).

2. All of the limiting countries allow for import of kosher/halal meat.

3. Judgment C-336/19 of the Court of Justice of the European Union made it possible for the state to prohibit the slaughter of animals without stunning even in the context of ritual slaughter. This may lead to legislative changes in the next years.

4. No countries have legal obligations to provide kosher/halal dietary adaptations in public institutions like schools, universities, hospitals, military, or penitentiaries.

5. In most countries, the actual provisions are not standardized at the central level and very much depend on individual institutions. Schools, universities, and military are usually the most adaptive to the requests of religious or belief minority members. However, most countries customarily provide or make efforts to provide either meals adapted to kosher/halal requirements, or without non-kosher/haram ingredients (see Map 2).

6. In most countries, there are no problems in bringing kosher/halal food from home or receiving it from third parties. Prisons are the most often exception, due to their penitentiary regimes.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Since many public institutions do not provide kosher/halal meat and do not allow to obtain it from alternative sources, offering a vegetarian option should be compulsory in public school, prison, healthcare institution, and Army canteens. However, it should be noted that this is not an optimal solution – for some strands of Judaism, meals cooked by non-Jews are not kosher, and thus require further adaptation.

2. Alternative solutions to the current pre-cut stunning should be sought that would comply with religious requirements without compromising animal welfare.

3. Allowing for bringing kosher/halal foods by third parties, including in penitentiaries, could be another way of promoting rights of religious minorities without significantly increasing the efforts required from public institutions.

What we are talking about

Ritual slaughter refers to a broad range of practices that involve slaughtering livestock in line with ritual norms and in a ritual context. While various cultures and religious traditions practiced ritual slaughter in some form over time, in the contemporary European context ritual slaughter has been predominantly associated with Jewish and Muslim communities and the kosher/halal meat production.

Based on Torah and Talmud, Jewish dietary regulations (Kashrut) differentiate between two types of food domains: plants and animals. While practically all plant foods are consumable, once they have been carefully inspected for contaminants, there are significant dietary restrictions concerning animal foods. For the animal to be considered kosher, it needs to have split hooves and chew its cud. Moreover, it needs to be slaughtered in a specific manner. A subset of Kashrut rules, schechita, dictates the rules according to which slaughter needs to be performed by a specially trained slaughterer, schoichet. The two basic rules for the slaughter to be kosher are:

1. The animal must be alive before the ritual begins.

2. The ritual follows a specific order, in which specific blood vessels must be cut in a specific place to ensure that the animal becomes unconscious and insensitive, with the use of a specific sharp tool called chalaf. The slaughter is then followed by an inspection of the body and the internal organs for abnormalities (terefot), and porging (nikur), which removes blood and excess fat.

Islamic dietary regulations divide foods into two basic categories: lawful (halal) and unlawful (haram) foods. This is supplemented by discouraged (makrooh) and suspected (mashbooh) foods. In principle, all foods are considered halal unless specifically designated haram in the Quran or Hadiths. Alcohol, pork, blood, dead meat, and meat that has not been slaughtered in line with the Islamic rules are explicitly forbidden in the Quran, while Islamic jurisprudence distinguishes more haram foods based on the interpretation of other passages in the Quran. Shari’ah, Islamic law, regulates the rules for the animal slaughter to produce a purified meat – zabiha or dhabiha – which led to concrete certification systems. These rules provide a complex set of guidance on issues such as halal breeding, animal welfare, stunning, slaughterer, the method of slaughtering, invocation, packaging, labeling, and, finally, retailing.

While both Jewish and Islamic ritual practices share a lot of similarities, they differ in one important aspect: the approach to stunning of the animal. While reversible stunning, post-cut stunning, and simultaneous stunning are discussed as possible within both traditions, the most effective method of stunning, pre-cut stunning, permanently damages the animal’s body, and thereby conflicts with the prescriptions that require the animal to be fully alive before the slaughter begins. The dominant interpretation of the Jewish law views it as a potential impairment of animal’s perfection, and thus forbids it. Islam is more divided on the issue, which means that some Muslims accept an animal killed with pre-cut stunning as halal, while others do not.

Thus, while both ritual practices account for animal welfare by attempting to minimize the suffering of the slaughtered animal, the opposition to pre-cut stunning led both traditions into conflict with the animal welfare movements. As the requirement to stun animals before slaughtering became the dominant principle, the exceptions for ritual slaughter began to be subject to negotiation. The earliest legislation forbidding ritual slaughter by requiring stunning dates to the 19th century and then was followed by on and off legislation in other countries in Europe. The issue has been complicated further, as many legislative proposals were introduced, supported, or promoted, by antisemitic movements, which, more recently, have acquired a more Islamophobic character. This led to the suspicions which proposals were just an effort at balancing animal welfare and religious freedom, and which were covert attacks on the latter.

According to a 2020 poll made by Savanta ComRes for the Eurogroup for Animals, the majority of Europeans supports the requirement to stun the animals before slaughtering, without exception for religious reasons (87% agree), although they want to prioritize funding for alternative practices that would comply with religious requirements without compromising animal welfare (80% agree). This is in line with the scientific consensus around the optimal methods for reduction of animal suffering (see reading suggestions below). In the last decade, Slovenia banned ritual slaughter altogether, while Denmark, Wallonia and Flanders introduced pre-cut stunning requirements. This led to significant criticism from Muslim and Jewish communities. For example, in response to the legislative proposals in Belgium, which required a reversible stunning procedure even in the context of ritual slaughter, several Muslim and Jewish organizations introduced an annulment appeal to the country’s Constitutional Court, which, in turn, referred a preliminary question to the Court of Justice of the European Union. The 2020 European Court of Justice judgment in the case C-336/19 sided with the Belgian region of Flanders, acknowledging the right of the EU Member States to prohibit slaughter without stunning, even in the context of ritual slaughter. This led to broad public discussion on the topic in the EU, including EU-wide consultations organized by the European Commission in 2022.

Five questions to the National Legal Experts

To provide a clearer picture of the current state of the legislation and practice concerning ritual slaughter the Atlas of Religious or Belief Minority Rights asked five questions to the National Legal Experts.

1. Is ritual slaughtering allowed in your country?

This question asks about the current regulations concerning exceptions for animal slaughter: no stunning required, post-cut stunning, simultaneous stunning, and pre-cut stunning.

2. If ritual slaughtering is forbidden, is importing from abroad ritually slaughtered food allowed?

As an alternative to the exceptions for religious slaughter, some countries, for example Denmark, proposed to allow for kosher/halal meat import.

3. Are public schools, hospitals, prisons, and the army obliged to provide halal or kosher food to students, patients, inmates, and military personnel who demand it?

This question asks whether individuals have the right to request specific dietary provisions within these institutions that comply with their religious requirements, which will oblige the institution to provide them.

4. If there is no obligation, is it customary to provide halal/kosher adaptations for students, patients, inmates, and military personnel who demand it?

This question asks about the actual provisions. The questions could have been answered in three ways: yes, halal/kosher food is customarily provided (a positive provision); yes, food without haram/non-kosher ingredients is customarily provided but not halal/kosher food (a negative provision); no, neither halal/kosher food nor food without haram/non-kosher food is customarily provided. We allowed for differentiation between institutions.

5. If there is no obligation, can students, patients, inmates, and military personnel consume halal or kosher food brought from home or provided by someone other than the public institution (e.g., their religious organization)?

Most kitchens within public institutions lack means for following strict rules of Kashrut. Thus, some institutions, for example some Austrian and Belgian penitentiaries, reach out to Jewish organizations to supply meals for their Jewish population.

Ryszard Bobrowicz

Focus Ritual Slaughter: Questionnaire

RESOURCES

For a review of different European legislative regimes see

United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (2020, October). Legislation Factsheet: Ritual Slaughter Laws in Europe

Eurogroup for Animals (2021, May). Slaughter without Stunning (Position Paper)

For databases of applicable legislation see

the Legislation Database of the Global Animal Law GAL Association

the FAOLEX Database of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation

For scientific approaches to stunning and animal welfare see

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) (2004, July 6). Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW) on a request from the Commission related to welfare aspects of the main systems of stunning and killing the main commercial species of animals.The EFSA Journal, 45, pp. 1-29

Ferraro, F. (2017). Ritual Slaughtering Vs. Animal Welfare: A Utilitarian Example of (Moral) Conflict Management, in M. Rawlinson, & C. Ward (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Food Ethics. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 305-314

For a brief review of the role of ritual slaughter for religious identity see, for example

Bonne, K., & Verbeke, W. (2008). Religious values informing halal meat production and the control and delivery of halal credence quality. Agriculture and Human Values, 25, pp. 35-47

Greenfield, H. J., & Bouchnick, R. (2010, January). Kashrut and Shechita – The Relationship Between Dietary Practices and Ritual Slaughtering of Animals on Jewish Identity, in L. Amundsen-Meyer, N. Engel, & S. Pickering (eds.), Identity Crisis: Archaeological Perspectives on Social Identity. Proceedings of the 42nd (2010) Annual Chacmool Archaeology Conference, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta. Calgary: Chacmool Archaeological Association

See also

https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/farm/slaughter/religiousslaughter

Messner, F. (ed.), Dictionnaire du Droit des Religions, s.v. «Abbatage rituel». Paris: CNRS Editions, pp. 3-17

Martínez-Ariño, J., & Zwilling, A-L (2020). Religion and Prison: An

Overview of Contemporary Europe. Cham: SpringerLerner, P., & Rabello, A. M. (2006). The Prohibition of Ritual Slaughtering (Kosher Shechita and Halal) and Freedom of Religion of Minorities. Journal of Law and Religion, 22(1), pp. 1–62